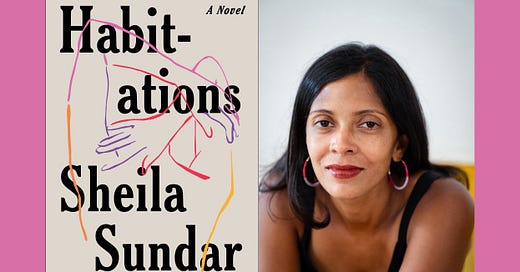

In Sheila Sundar’s novel Habitations, (Simon & Schuster, April 2, 2024), Vega Gopalan leaves her native India in search of a new start in the U.S. She’s seeking an advanced degree in sociology but she’s also fleeing a disastrous love affair and the death of a beloved sister. Over the course of a decade, she will move many times, in and out of relationships, up and down the academic ladder—but always in search of what might feel like home.

“We’re allowed to want different things at different times,” one of Vega’s lovers tells her. “We’re allowed to be happy, even if it’s not what we thought happiness would look like.” But do we get second chances at happiness? Endless chances?

Unexpected motherhood requires Vega to make hard choices about the kind of life she wants to build for herself and her daughter, but it also forces her to confront the grief she thought she had put behind her. Sundar shows some of the many ways love and family can form and the unexpected places where home can be found. Habitations is a novel brimming “with immediacy, warmth, and wry humor,” writes Ha Jin (National Book Award winner of Waiting), and is “a significant addition to migrant fiction.”

Sheila Sundar is a professor of English and creative writing at the University of Mississippi and lives in New Orleans with her husband and their three children. Her writing has appeared in The Virginia Quarterly Review, The Massachusetts Review, The Threepenny Review, and elsewhere.

Kernel editor Sarah Ligon spoke with Sundar on a sunny morning last March in Sundar’s office at the University of Mississippi, where Sarah is a student in the MFA program.

[Editor’s note: This interview was edited for length and clarity.]

Sarah Ligon: How did you come to writing as a career? It was not a very direct path, I think.

Sheila Sundar: It wasn't. I was writing for many, many years in the margins. I had this vision that success was being a part of that “25 under 25” list. Then later “35 under 35.” Well, I was never going to be that.

I went to grad school in education shortly after college, and I became a teacher and was very committed to being a teacher, but I also wanted to be a writer. So shortly into my teaching career, when I felt stable about it, I started taking writing seriously. I was in New York City, and I took courses with the Gotham Writers Workshop, and I formed a writing group. Writing was always this thing I did but, in the same way that people who are passionate about knitting or a sport pursue those things, as a recreational activity.

After I had kids, the whole ground moved underneath. I had a career change. We moved around as a family. I look back and some years I didn't get to the writing. But over the course of many, many years I wrote a book that was about 500 pages. I spent ten years learning how to write a novel, and I thought the greatest intellectual loss I could experience would be to not publish this book. Looking back, I'm really grateful that I did not publish it, because I made really fundamental mistakes.

What kinds of mistakes?

Instead of understanding character, I added a lot of external drama. I had written this really endearing protagonist: she was funny, she was a mess, and she was narrating all of this political change around her but had no sense of her privilege. I had written maybe a hundred pages before I asked myself, I wonder what this book's gonna be about? But instead of going back and understanding her better, I made a lot of plot moves in order for her to react to them. So I was like, “Well, this isn’t dramatic enough, so now she has to bear witness to this.” Then I would tack on 20 more pages, then 20 more, then a hundred more. The novel became so bloated. These were mistakes that I couldn't necessarily undo because they were so sewn into the fabric of the novel.

“... [I]f there isn't sufficient tension in your book, don't add plot moves. Go back and write that tension internally.”

What I learned from that was that if there isn't sufficient tension in your book, don't add plot moves. Go back and write that tension internally. That is the basic cake recipe. If you can write a story where there's less external tension but more internal drama, then you're a competent fiction writer and you're not leaning on the horrors of the world to make your characters matter.

Was not publishing it as bad as you had imagined it would be?

Well, no, because out of that novel came some sections that I was really proud of, some language that I thought was beautiful, some really memorable characters. What it was helpful for was that it got a couple of small awards, and it was the excerpt with which I got into grad school. So it served me in a lot of ways, in immediate ways, and also more fundamentally creative ways. Through those mistakes I learned quite a bit about what didn't work.

“Through … mistakes I learned quite a bit about what didn't work.”

How did you make the transition from part-time writer to published writer?

Eventually there was a point where I got good enough at writing and my kids were old enough for me to say, “I'm now going to actually pursue this.” They were six, eight, and ten at the time when I decided to apply to grad school. I’ve been meaning to ask if this was true for you, too, but there was really only one program I could have gone to that I was really excited about.

Yes, there was only one program I could have attended, and I felt I had to wait until my kids were old enough. They were three, nine, eleven, and thirteen when I applied to the University of Mississippi.

For me, that was the MFA program at Boston University. It was the right program by design. It was the right program in terms of duration [one year]. It was the right program in terms of faculty. But you can't really apply to just one program. The level of serendipity and subjectivity and competition is enormous. So anybody reading this should not follow either of our paths!

But you did get in!

I did, but I was so nervous about it. What if, at the end of an MFA, I had nothing to show for it? What if I couldn't crack how to write and sell a novel? But I had also come to the realization that if I didn't at least try to become a novelist, that I wouldn't be really happy, that everything would feel like a compromise. So it felt worth the gamble, worth the risk of pouring all of myself into it.

That’s an enormous juggling act: attending graduate school in Boston with three young children back home in New Orleans. How did you manage it?

What it allowed me to do was go to Boston when the semester was in session and fly home every other weekend. And it was really really hard. But it meant that the time that I was in Boston I wrote. I wrote, I wrote, I wrote. I wrote around the clock, and all I thought about were my workshop submissions and my stories. And when I was home with my family, I was fully present for them.

How did your MFA experience help you become a better writer?

What happened creatively in that year was that I arrived with a sense of a voice, but I didn't have a sense of the distinction between what made good writing and what made good reading. So a very clear goal emerged, which is that I wanted to write a book that was good reading—that served my reader, that my reader enjoyed and did not want to put down.

That was a different level of commitment because I no longer felt like I was writing for myself and for the story that I wanted to tell. But I was really writing in service of this imaginary reader, who was reading this with a hunger, and I wanted them to feel immersed in this world.

“I no longer felt like I was writing for myself …. I was really writing in service of this imaginary reader… .”

Were there books that had that quality, that were models for you?

I had five books I felt that way about: The Great Believers by Rebecca Makkai, An American Marriage by Tayari Jones, The Leavers by Lisa Ko, Animal Dreams by Barbara Kingsolver, and Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. They are immersive contemporary books, and I love them all for different reasons. I would go to them like, how did Kingsolver use dialogue to make me believe that this couple is real, and not a couple that she just concocted? How did Jones have these characters riffing off each other conversationally? How did Adichie move the narrative from place in a way that felt effortless to a reader?

And did you write Habitations while doing your MFA?

I emerged from the program with a short story that I knew was going to be the start of my novel, and when the program ended I just threw myself into the task of writing. I had developed a draft, a pretty flat draft, but it was a draft.

Then I felt that Vega, my protagonist, she's not smart enough. She's not alive enough. She's not aggressive enough in pursuit of her desires: her intellectual desires, her sexual desires, her familial desires, her social and emotional desires. I wanted to make her more vibrant on the page. I felt she was swimming beneath the surface of the book, and with each draft I pulled her closer and closer to the surface until I felt the reader could touch her.

“I felt [my protagonist] was swimming beneath the surface of the book, and with each draft I pulled her closer and closer to the surface until I felt the reader could touch her.”

Let's talk about revision. I’ve heard you say that after you wrote the first draft of Habitations, you opened a new blank document and started writing again from the beginning. This terrified me when I first considered it. I have done that for short stories, but for a novel it seems daunting. Tell me what your revision process looked like for this novel.

I knew I had the seed of an idea and that there were some good enough lines, but I also knew that if I tried to use that document I would have worked too hard to hold on to them at the expense of the larger narrative. So I printed out the full draft and highlighted the things I thought were good writing, that I wanted to hold onto—and many of them made it into the final draft—and I noted sections where I thought Vega, my protagonist, was pretty true to herself, and then I started writing again from the beginning.

My starting point was a pretty skeletal idea: I knew where Vega was from, that she was an academic, that she'd had this affair, but I didn't know her enough to narrate her life with any real emotional honesty. For my second draft, the focus was to make sure everything had emotional truth to it.

“For my second draft, the focus was to make sure everything had emotional truth to it.”

Vega, is an academic, an immigrant, a wife, a daughter, a mother navigating these often-competing loyalties. I'm curious if, in your own life, you've ever felt pulled between responsibility to your art, yourself, and your family?

Well, writing is one of those things where so much of it happens when you're not doing it: when you're driving or cooking or walking. Sometimes I have felt like the best stretches of writing are when I close the door and I'm only thinking about writing—and the best stretches of mothering are when I'm really present and I'm not worrying about my book. But another truth is that I don't know that I could have written this book if I hadn't ever loved my parents, loved my siblings, loved my partner, and loved my children in a way that you really don't think is possible until they show up.

So I think that there are two answers that seem in conflict but that are actually side by side. You do need to clear the space to write. For instance, if I make dinner in the morning and I set it aside, I'm not spending all my writing time with that mom ticker constantly going: “What am I going to make for dinner?” I'm able to calm that down. The immediacy of domestic labor, I have to just push that out of the way when I'm writing. But the larger world of caring for people is something that will always inform my work. I can't undo that part of it. I don't want to.

Inspiration, Information, & Insight

This week Sarah read two books that reminded her how much bigger the world of literature is than her own rather narrow reading tastes. For the undergraduate class where she’s a teaching assistant, she read Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris, and while science fiction is definitely not her cup of tea, she admired the worldbuilding that went into constructing a distant planet covered in a sentient ocean. For her graduate literature seminar, she read Monique Roffey’s Archipelago, about a grieving father, his young daughter, and their dog, who sail from Trinidad to the Galapagos Islands, and was impressed by how Roffey wrote the dog as a central character, carrying nearly equal narrative weight to the human characters. (If you know of other adult novels where animals are central figures, please drop a note in the comments!)

Shelby took a staycation leading up to her birthday in order to focus on getting her novel draft to completion. It’s not there yet, but Shelby’s happy with the progress she has made! She also decided to start re-reading her all-time favorite book Dandelion Wine by Ray Bradbury. While Bradbury is most notably known for his science-fiction writing, Shelby stands her ground when she says that Dandelion Wine—a novel that centers on characters in a small town, USA, which is loosely based off of Bradbury’s childhood and hometown Waukegan, IL—is his best work. (And yes, she has read most of his oeuvre!) His prose infuses emotions and evokes beauty. Take this line, for example: “They departed like the pale fragments of a final twilight in the history of a dying world.”

Neidy drove from New York to South Carolina with her sons, her mother, and her mother's two dogs! She spent the week hanging out with her dad, her sister-in-law, and her newest niece. Between all the family time she beta read a writer friend's novel.

Natalia wrote and submitted a grad school application—a 15-page research paper on cancel culture and book banning, and a statement of purpose. The joy of being done naturally fed into the joy of the Easter season.

So many great insights in this kernel! Best of luck to Shiela Sundar on her launch!

A delightful and eyeing-opening interview. I’m always curious about writers’ path and process, especially those who navigate it mid-life with partners, children, and other entanglements. As for Sarah’s animal question, isn’t Virginia Woolf’s Flush an example?